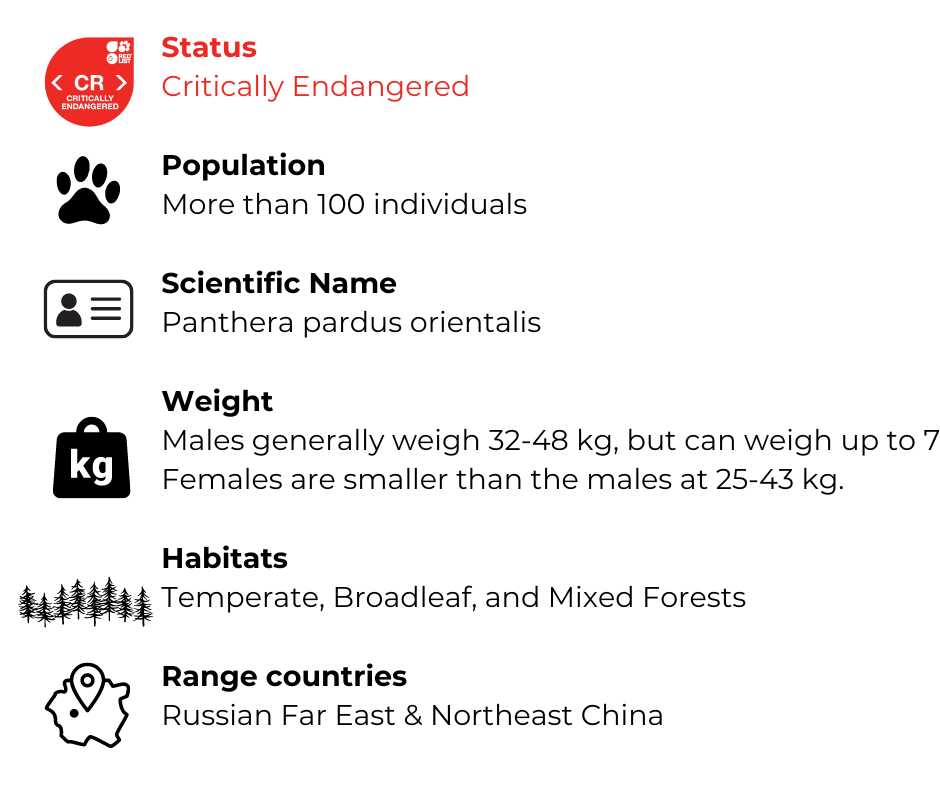

The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is a leopard subspecies native to the Primorye region of southeastern Russia and northern China. It is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, as in 2007, only 19–26 wild leopards were estimated to survive in southeastern Russia and northeastern China.[1]

As of 2015, fewer than 60 individuals were estimated to survive in Russia and China.[4] Camera-trapping surveys conducted between 2014 and 2015 revealed 92 individuals in an 8,398 km2 (3,242 sq mi) large transboundary area along the Russian-Chinese border.[5] As of 2023, the population was thought to comprise 128–130 sub-adult and adult individuals.[6]

Results of genetic research indicate that the Amur leopard is genetically close to leopards in northern China and Korea, suggesting that the leopard population in this region became fragmented in the early 20th century.[7] The North Chinese leopard was formerly recognised as a distinct subspecies (P. p. japonensis), but was subsumed under the Amur leopard in 2017.[3]

Where do Amur Leopards live?

Amur leopards prefer to live in areas with mixed Korean pine and deciduous forest while avoiding open grasslands or populated areas.

They are now only found in the border areas between the Russian Far East and north-east China, and possibly North Korea. Most Amur leopards are in Russia, with a few in China. Their range is smaller than 2,500 sq km—that’s an area smaller than Dorset.

Why Amur leopards are so important

Amur leopards are top predators in their landscape, so they’re crucial role for keeping the right balance of species in their area. That also affects the health of the forests and wider environment, which provides local wildlife and people with food, water and other resources.

FACTS

FACTS

The Amur Leopard or Far Eastern Leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is one of the eight subspecies of leopard. It is only found in the Russian Far East and North East China and the latest population census taken in 2017 suggests there are now around 100 individuals.

As recently as the 1970s, their population in the wild had dwindled to fewer than 30 individuals, making the Amur leopard is one of the world’s most endangered big cats and for this reason it is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, and CITES Appendix I for protection status.

Naming and etymology

The names ‘Amurland leopard’ and ‘Amur leopard’ were coined by Pocock in 1930, when he compared leopard specimens in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London. In particular, he referred to a leopard skin from the Amur Bay as ‘Amur leopard’.[8] Since at least 1985, this name has been used for the leopard subspecies in eastern Siberia and for the captive population in zoos worldwide.[9][10]

The Amur leopard is also known as the “Siberian leopard”,[11] “Far Eastern leopard”,[12][13][14] and “Korean leopard”.[15]

Taxonomic history

In 1857, Hermann Schlegel described a leopard skin from Korea under the scientific name Felis orientalis.[16] Since Schlegel’s description, several naturalists and curators of natural history museums described zoological specimens of leopards from the Russian Far East and China:

- Leopardus japonensis described and proposed in 1862 by John Edward Gray was a tanned leopard skin received by the British Museum.[17]

- Leopardus chinensis proposed by Gray in 1867 was a leopard skull from the mountains northwest of Peking.[18]

- Felis fontanierii proposed by Alphonse Milne-Edwards in 1867 was a leopard skin from the vicinity of Peking.[19]

- Felis ingrami was a leopard skin from Kweichow in central China, and Felis villosa a leopard skin from the Amur Bay, both proposed by J. Lewis Bonhote in 1903.[20]

- Felis [Leopardus] grayi proposed in 1904 by Édouard Louis Trouessart was a leopard fossil.[21]

- Panthera hanensis proposed in 1908 by Paul Matschie was a leopard skin from Shaanxi province.[22]

- Felis pardus sinensis proposed in 1911 by a German fur trader was a leopard skin from southern China.[23]

- Panthera pardus bedfordi proposed in 1930 by Reginald Innes Pocock was a leopard skin from Shaanxi.[8]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group subsumed P. p. japonensis to P. p. orientalis. The remaining synonyms are not considered valid subspecies.[3] However, a 2024 study which performed phylogenetic analysis on the basis of cranial morphology and mitochondrial genome analysis suggested that P. p. japonensis is likely a distinct subspecies.[24]