The great auk (Pinguinus impennis), also known as the penguin or garefowl, was a fascinating flightless bird that sadly went extinct in the mid-1800s. It first appeared around 400,000 years ago and was the only modern species in its genus, Pinguinus. Interestingly, even though it was often called a “penguin,” it wasn’t actually related to the penguins we know today from the Southern Hemisphere. Those birds were named “penguins” simply because they looked a lot like the great auk — not because they were related.

About Great auk

The great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was a large, flightless seabird that sadly went extinct in 1844. These birds were part of the Alcidae family (from the order Charadriiformes) and were once found in big colonies on rocky islands along the North Atlantic — places like St. Kilda, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Funk Island near Newfoundland. Interestingly, even though they lived up north, scientists have found their remains as far south as Florida, Spain, and even Italy, which gives us a glimpse into how far they may have once wandered.

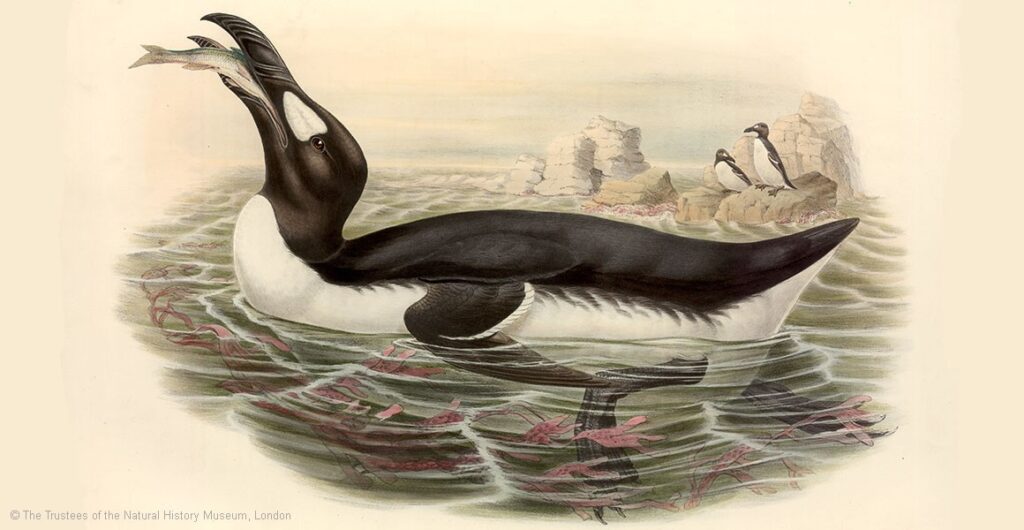

The great auk was a fairly big bird — about 75 cm (or 30 inches) tall. Even though it couldn’t fly, it was an excellent swimmer, using its small wings (less than 15 cm long) like flippers to move through the water. It had a large, black beak with several grooves running across it — kind of like natural ridges.

When worlds collide: the lesson of the great auk

Pictured below is the last remaining specimen of a British great auk, a flightless seabird driven to extinction in the nineteenth century.

Great auks were once common in the waters of the North Atlantic.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), great auks didn’t live all bunched up in one place — they were spread out in small colonies across the ocean. When it came time to breed, they were pretty picky and chose only remote, rocky islands as their nesting spots. You could find them raising their young around places like Canada, Greenland, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and the UK — far from people, tucked away in the wild.

Even though great auks looked a lot like penguins, they weren’t actually related. But they did have a few things in common — for one, neither of them could fly! And just like penguins, adult great auks spent a lot of their time diving underwater, hunting for fish to eat.

The death of a species

Unfortunately, the great auk didn’t disappear because of losing its home, but because of people hunting them too much. They were hunted for their feathers, meat, fat, and oil. Sadly, the very last great auk was spotted in 1852, after most of the others had already been wiped out.

European fishermen and whalers devastated the largest colony, in Newfoundland, despite a petition in 1775 to stop the massacre.

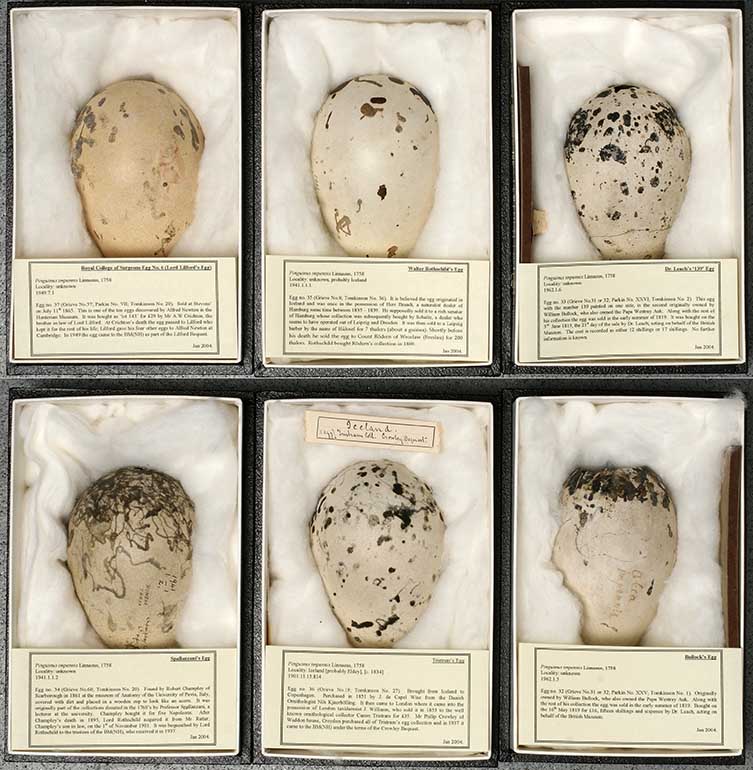

Back in the early 1800s, great auks had become really rare, and that actually made them even more valuable. Collectors were willing to pay big money just for a single egg or a piece of their skin. Sadly, this demand from museums and collectors did the species in. In 1844, the last breeding pair tried to escape hunters, but they couldn’t get away — and to make things worse, their one and only egg was destroyed too.

Douglas Russell, the Senior Curator of Birds at the Museum, reminds us that the challenges our plants and animals face today are just as big — maybe even bigger — than when we lost the great auk. He points out that the great auk’s disappearance, only a few generations ago, was the result of many years of humans overusing and exploiting them without stopping.